Writing The Desecration of England

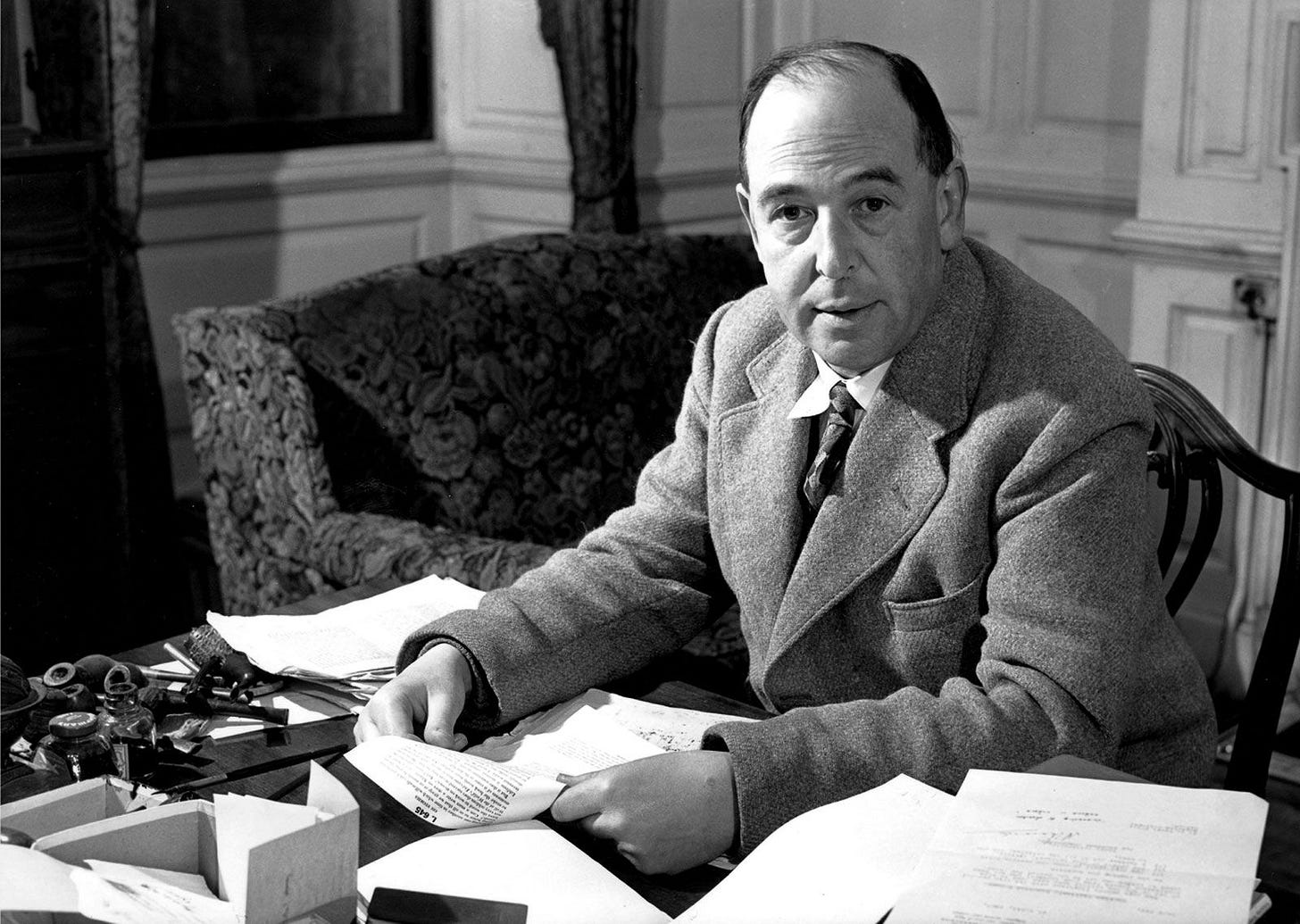

How the poetic works of C.S. Lewis warned of what would happen if the traditions, myths and ways of life native to the UK were destroyed.

The works of C.S. Lewis were absent from my childhood - and I struggle to consider the few instances where I saw film versions of various Chronicles of Narnia instalments as part of that. As I have gone through my twenties, however, I’ve come closer and closer to delving into his works. On December 18th 2024, I finished C.S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength for the first time, on recommendation from

and ’s excellent lecture series on the books.Reading it as part of a complete trilogy, beginning with Out of The Silent Planet and then progressing to Perelandra, it was obvious to me why Cynthia felt so compelled to talk about these books. Over the three books, Lewis provides a brilliant critique in allegorical form of eugenics, moral relativism, and state totalitarianism in the name of “science” that began it’s rise in Lewis’ time and, arguably, is coming to full fruition now. I won’t say too much more on it here, mainly as Cynthia has already highlighted so many of its gems more eloquently than I could have done.

What particularly jumped out in my reading was the sense of soul and connection to the divine that characterise the protagonists forming company with the Pendragon - unlike the antagonists of the National Institute of Co-ordinated Experiments (N.I.C.E), who all attempt to narrow the definition of what constitutes life, in order for them to control it. This connection to the divine also necessitates a reverence for the mythology and lore that has made the towns of England what they were in that day, made intrinsic to the plot in the resurrection of Merlin, from Arthurian legend. The Pendragon company understand this, but the N.I.C.E are all too willing to destroy and desecrate the parts they cannot objectively rationalise, all in pursuit of their own transhumanist desires.

Lewis explored these themes across many of his writings, including his poetry, which is often overlooked considering his many other works that have (rightfully so) garnered praise. The very nature of poetry forces poets to convey their message in concise, yet beautiful and imaginative ways. Delving into his poetry following my completion of That Hideous Strength, I found that Lewis was able to do this with his own sentiments regarding the times in an incredibly powerful way, and I felt compelled to share them with the wider world in the hope that more may benefit from his insights.

I’ve selected just three that have something poignant to say about our modern condition, what we have done, and how we might heal.

I won’t include the full text of each poem in the body of the article directly, but I will link to places where the texts are available publicly for you to read at your own leisure.

The Condemned

Lewis’ concern for the increasing destruction of countryside life, and its replacement by the soullessness of industrial cities and politics, is one he shared with his close friend at Cambridge, J.R.R. Tolkien. And, it’s on full display in The Condemned in a particularly pessimistic manner.

We see that it’s not just the nature itself that is under attack, but the rich history of poets and people who put words to its magic, which Lewis makes explicit reference to. Their rich traditions and reverence for the man-nature connection is being gassed out like vermin, along with the spirit of England itself, in the pursuit of “progress” and of a caged, ordered, and highly controlled society. The relics of its culture are thus relegated to the “zoo” of entertainment as some outdated antiquity, and to create propaganda about how man with its “Guns, Ferrets and Traps” has triumphed over the “strange”.

It paints a sad picture - but there is still hope in my eyes. We’re seeing a rise of populism and grassroots protest movements, as the spirit of England comes increasingly under attack by postmodern and globalist agendas pursued by councils and governments. Here are ordinary people defending the “wildness” in England - its grassroots, communal spirit, and the right of an Englishman to have a home as his castle and to be free to work with its rich land. And it seems to be working. If Lewis is right that it cannot be tamed, then really it is the “Ministry” and its totalitarian desires that are “condemned”.

The Country of the Blind

Throughout his life, Lewis was highly critical of the mechanistic view that writers took on human beings and life, in particular H.G. Wells. Indeed, much of Lewis’ Science Fiction Trilogy responds directly to works like The First Men in the Moon, heavily modelling the antagonists of the various books on the protagonists of Wells. And I suspect Lewis’ The Country of the Blind intends to dig at Wells’ work of the same name.

To me, the comparison to the scientific “experts” dominating the world in recent years is a clear example of the phenomena described by Lewis in this poem - not just through Covid, but also in the disguise of political activism as “social sciences”. Despite literally “losing sight” of important aspects of the human experience, the subjects of Lewis’ poem endeavour to say they are better than those who’ve retained their sight. With “tricks of the phrase”, they posture their “abstract thoughts” and pretend to know of the “green-sloped sea waves” they have never truly known. Moreover, they have no desire to understand it fully; they are “mouldwarps”, living underground, contempt in “attempt[ing] speech on the truths” from within their narrowed view of life, explaining the views of others away with increasingly convoluted rationalisations of their own.

And yet, it is not a wilful blindness in many cases - hence why “it was worse” than if one had actually questioned the descriptions being brought to them, rather than retorting to a generic dismissal of “we’ve all felt just like that”. The moral blindness has been a “slow curse” through the centuries, through which people have forgotten what it is to breathe and go forth with a full appreciation of life. So many have been willing to comply with the authoritarian dictats of the past few decades, and why so many either buy the propaganda of warmongerers and perverts or submit to the idea that this is just the way things are.

For me, this poem is a call-to-action for us to truly see the world - to explore the merits of what our culture has lived through with openness that there may be something important we’ve been blind to. We need to see, once more, the corners of England unspoilt by the pursuit of a cultureless, soulless, globalist scientism - the kind of England under destruction in The Condemned. There are things worth conserving here - as our final poem will explore.

The Future of Forestry

The line that hit me hardest on my first readthrough of this was “What was Autumn? They never taught us.”

If The Condemned is about what is happening, and The Country of the Blind is about how it has gotten to this point, then The Future of Forestry is the reason why it is worth making a stand for the traditions and native culture of England. We’re warned of a world with no real access to the nature that inspired our ancestors and thinkers - and where the only reference to them is in records of old.

It’s a shame that, in a way, we’re already there. Significant swathes of children living in cities have never been to the countryside, with its “elm” and “chestnut”. And then combine this with a lack of local community in which to share that joy, and it makes for a deadly combination.

It’s no wonder that so many - including myself - have turned to online communities to get a sense of that shared joy, with it being so difficult to find in-person anymore. But the online world is not the real world. The temptation, therefore, is to make ourselves acceptable to the abstracted online universe we inhabit; a world of fake narratives and finding the next outrageous and dangerous fad to hop on to. In this world, there is no divinity and sacredness of the self - and indeed, we are encouraged to literally sell our souls for the gods of algorithms and internet clout.

Nature doesn’t work in the same way. Nature couldn’t care for the whims of the moment. Nature doesn’t thrive off of who can achieve moral decay the flashiest. Nature is about permanence and true connection. Nature is about the respect for life and its manifestation, not the poisoning and desecration of it. It inspires us to grow, rather than to reside as a diminished version of ourselves.

With that in mind, the “Future of Forestry” is, really, the future of us. Will we choose choose to cut the tree of our life short by allowing the beauty of nature and history to be destroyed? Or will we nurture it, conserve it, and enjoy the fruits of that labour for generations to come?

I hope it will be the latter.

.

And what was [poetic imagination] (?), they never taught us.

Is there any just consequence for this crime?

Me.

Blake punishes me for my unjustifiable blindness in the face of great beauty by torturing from me tears of sight, rememberance, and agapé.

Tom,

you awaken poetic imagination. Poetic imagination is not trivial. It breathes beauty.

Imagine having a chat with some great poets.

https://youtu.be/9Q22wg9_54g?si=86NI4EhzGjGMN-vm

.