This piece is part of my ongoing translation of the novel of Thea von Harbou’s “Metropolis”. If you’d like to find out more about the project and get quick links to the other chapters, check out the essay below:

There was a house in the great Metropolis older than the city. Many said it was even older than the Cathedral, and that, before the Archangel Michael raised his lungs as a voice in the fight for God, the house stood there in its evil gloom and defied the Cathedral with its clouded eyes.

It had lived through the time of smoke and soot. Every year that passed by the city, in its dying, seemed to crawl into this house, such that it ultimately became a cemetery—a coffin filled with dead decades.

Set into the black timbers of the door stood, copper-red and mysterious, the seal of Solomon—the pentagram.

It was said that a sorcerer who came from the East (with a pestilence following in the footsteps of his red shoes) had built the house in seven nights. But the bricklayers and carpenters of the city did not know who had mortared the bricks, nor who had erected the roof. No foreman’s speech and no ribboned bouquet had sanctified the topping-out ceremony, as is pious custom. The chronicles of the city held no account of when or how the sorcerer died. One day it struck the citizens as strange that, for so long, the red shoes of the sorcerer had shunned the hideous plaster of the town. They barged into the house and found no living soul inside. Receiving neither by day nor by night a ray from the great lights of the sky, the rooms seemed to be engulfed in sleep, waiting for their master. Parchments and folios lay tossed about, covered in dust like silver-grey velvet.

Set into all the doors stood, copper-red and mysterious, the seal of Solomon—the pentagram.

Then came a time for tearing down the old. As such, the remarks arose: the house must die! But the house was stronger than these remarks, just as it was stronger than the centuries. It slew those who laid their hands on its walls with a sudden falling of stones. It opened up the floor beneath their feet and dragged them down into a shaft which nobody had any previous knowledge of. It was as though the pestilence, which once wandered in the wake of the red shoes of the sorcerer, still crouched in the corners of the narrow house, springing at the men from behind in the neck. They died, and no doctor recognised their illness. The house resisted its destruction so hard and with so great a force that word of its malignity got out beyond the borders of the town and far across the land until, eventually, there was no honest man to be found who would have dared take up arms against it. Yes, even the thieves and rogues, who were promised remission of their sentence, provided they declared themselves ready to tear down the sorcerer’s house, would rather go to the pillory or even to their execution than into the might of these spiteful walls, and through these latchless doors sealed with Solomon’s seal.

The little town around the Cathedral became a big city, growing into Metropolis and into the centre of the world. One day, a man from far away came to the city, saw the house and said: “I want to have that.” He was introduced to the history of the house. He did not smile. He stood by his resolution. He bought the house at a very low price and moved in immediately, keeping it unaltered.

The man was called Rotwang. Few knew him. Only Joh Fredersen knew him very well. It would have been easier for him to have chosen duking-out the fight over the Cathedral with the sect of Gothics rather than fight with Rotwang about the sorcerer’s house.

In Metropolis—in this city of reasoned and regulated hurry—there were very many who would rather go well out of their way than have to go past Rotwang’s house. It barely reached to the knees of the house-giants which lay near it. It stood at an angle to the street. To the clean city, which knew neither smoke nor soot, it was a blot and an annoyance. But it remained standing. If Rotwang left the house and crossed the street, which occurred but seldom, there were many who covertly looked at his feet to see if, perhaps, he walked in red shoes.

At the door of this house, on which the seal of Solomon glowed, Joh Fredersen, master of Metropolis, stood.

He had sent the motor-car away, and he knocked.

He waited, and knocked again.

A voice asked, as though the house spoke in its sleep: “Who is there?”

“Joh Fredersen,” said the man.

The door opened.

He entered. The door closed. He stood in darkness. But Joh Fredersen knew the house perfectly. He went straight on, and as he went, two shimmering traces of striding feet lit up on the tiles of the corridor in front of him, and the edge of a stair began to glow. Like a dog on the scent, the glow ran up the stairs in front of him and died out behind him.

He reached the top of the stairs and looked around him. He knew that many doors opened out here. But on the one opposite him, the copper seal glowed like a distorted eye that looked upon him.

He stepped up to it. The door opened before him.

Of the many doors that Rotwang’s house also possessed, this was the only one which opened itself to Joh Fredersen, even though—and perhaps, even, because—the owner of this house knew full well that it never took any semblance of effort for Joh Fredersen to cross this threshold.

With a sharp sound, the door snapped shut behind him.

He drew in the air of the room, tentatively but deeply, as though he sought the trace of another breath within it. His indifferent hand threw his hat on a chair. Slowly, in sudden and sad weariness, his eyes wandered the room.

It was almost empty. A large, time-blackened chair, like those found in old churches, stood before drawn curtains. These curtains concealed a recess as wide as the wall.

Joh Fredersen remained standing by the door for a time, without stirring. He had closed his eyes. With an unparalleled agony, he breathed in the odour of hyacinths, which seemed to fill the motionless air of this room. Without opening his eyes, swaying a little, but purposefully, he went up to the heavy, black curtains and drew them apart. Then he opened his eyes and stood quite silently…

On a pedestal, the width of the wall, rested the stone head of a woman. It was not the work of an artist; it was the work of a man who, in agonies for which the human language lacked words, had wrestled through immeasurable days and nights with the white stone, until it seemed as though the white stone was finally understood, and the shape of a woman’s head formed by itself. It was as if no tool had been at work here—no, it was as if a man lying before this stone, unceasing, with all the strength, all the longing and all the despair of his brain, blood and heart, had called upon the name of the woman until the unshaped stone took pity on him, letting the image of the woman, who—to two men—had meant all of Heaven and all of Hell, arise from itself.

Joh Fredersen’s eyes lowered to the words which stood crudely etched into the pedestal, as though chiselled under curses.

Hel

Born for my happiness,

a blessing to all men.

Lost to Joh Fredersen.

Died as she gave life

to his son, Freder.

Yes, she died then. But Joh Fredersen knew only too well that she did not die from giving birth to her child. She died then because she had done what she had to do. In reality, she died the day she went from Rotwang to Joh Fredersen, surprised that her feet left no bloody marks on the way. She died because she was unable to withstand the great love of Joh Fredersen and because she had been forced by him to tear another’s life down the middle.

Never had the expression of final redemption been stronger upon a human face than upon Hel’s face when she knew that she would die. But in the same hour, the mightiest man in Metropolis had laid on the floor screaming, like a wild beast whose limbs were being broken while it was still alive. And, when he met Rotwang four weeks later, he found that the thick and feral hair over the wonderful brow of the inventor was snow-white, and in the eyes under this brow the smouldering of a hatred very closely related to madness.

In this great love, in this great hatred, the poor, dead Hel had stayed alive for both men.

“You must wait a little while,” said the voice, sounding as though the house was talking in its sleep.

“Listen, Rotwang,” said Joh Fredersen, “you know that I have patience for your trickery and that I come to you if I want something from you—and that you are the only man who can say that of himself. But you will never get me to play along with you when you play the fool. You know, too, that I have no time to waste. Don’t ridicule us both—so come!”

“I told you that you would have to wait,” explained the voice, seeming to grow more distant.

“I will not wait—rather, I shall go.”

“Do so then, Joh Fredersen!”

He wanted to do so. But the door through which he had entered had no key and no latch. The seal of Solomon, glowing copper-red, blinked at him.

A soft, distant voice laughed.

Joh Fredersen had stopped still, his back to the room. A quiver ran down his back, running along his hanging arms to his clenched fists.

“One would have your skull smashed in,” said Joh Fredersen very softly. “One would have your skull smashed in, were it not holding such a valuable brain.”

“You can do no more to me than you have already done,” said the distant voice.

Joh Fredersen was silent.

“Which do you think,” continued the voice, “would be more painful: to smash the skull in, or to tear the heart out of the body?”

Joh Fredersen remained silent.

“Is your wit frozen thus that you don’t answer, Joh Fredersen?”

“A mind like yours should be able to forget,” said the man standing at the door, staring at Solomon’s seal.

The soft, distant voice laughed.

“Forget? I have twice forgotten something in my life. First, that Etro-Oil and mercury have an idiosyncrasy towards each other; that cost me my arm. Second, that Hel was a woman and you a man; that cost me my heart. The third time, I fear, will cost me my head. I shall never forget anything again, Joh Fredersen.”

Joh Fredersen remained silent. The distant voice was silent, too.

Joh Fredersen turned around and walked to the table. He stacked books and parchments on top of each other, sat down and took a piece of paper from his pocket. He laid it before himself and looked at it. It was no larger than a man’s hand, bearing neither print nor script, and was covered over and over with the sketching of a strange symbol and a seemingly half-destroyed plan. Routes seemed to be indicated on it which seemed like wrong routes, but they all led to one destination: a place which was filled with crosses.

Suddenly, he felt a gentle but certain coldness approaching him from behind. Involuntarily he held his breath.

A hand reached past his head—a delicate, skeletal hand. Transparent skin was stretched over the slender joints, which shimmered beneath it like dull silver. Fingers, snow-white and fleshless, closed over the plan which lay on the table, lifting it up and taking it away with them.

Joh Fredersen spun around. He stared at the being which stood before him, with eyes that glazed over.

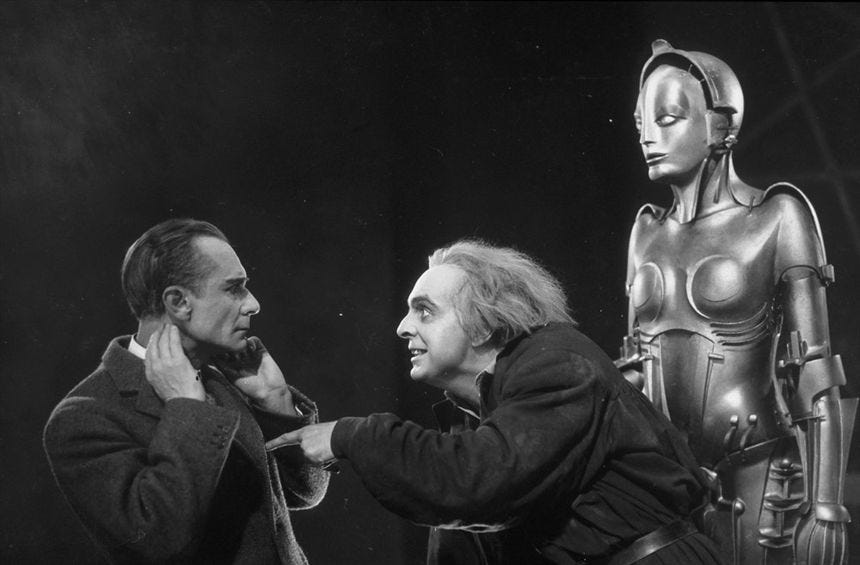

The being was, undoubtedly, a woman. In the soft garment which it wore stood a body like the trunk of a young birch tree, swaying on set-together feet. But, although it was a woman, it was not human. The body seemed as though made of crystal, through which the bones shone silver. Cold streamed from the glass skin which contained not a drop of blood. The being held its beautiful hands, with a gesture of determination and almost in defiance, pressed against its breast, motionless. And yet, the being had no face. The beautiful curve of the neck bore a lump of carelessly-shaped mass. The scalp was bald, with nose, lips and temples barely indicated. Eyes, as though painted on closed lids, stared unseeingly, with an expression of calm madness, at the non-breathing man.

“Be courteous, my beautiful Parody,” said the distant voice, which sounded as though the house were talking in its sleep. “Greet Joh Fredersen, the master over the great Metropolis!”

The being bowed slowly before the man. The mad eyes neared him like two darting flames. The clump of head began to speak; it spoke in a voice full of a horrible tenderness:

“Good evening, Joh Fredersen.”

And these words were more enticing than a half-open mouth.

“Good, my pearl! Good, my crown jewel!” said the distant voice, full of praise and pride.

But in the same moment the being lost its balance. It toppled, falling forward towards Joh Fredersen. He stretched out his hands to catch it, and in that moment of contact felt burnt by an unbearable coldness, the brutality of which brought up a feeling of anger and disgust in him. He pushed the being away from him and towards Rotwang, who was standing near him as though having fallen from the air.

Rotwang took the being by the arm. He shook his head.

“Too intense!” he said. “Too intense! My beautiful Parody, I fear your temperament will play tricks with you.”

“What is that?” asked Joh Fredersen, leaning his hands against the the tabletop, which he felt behind him.

Rotwang turned his face towards him, in which glorious eyes glowed like watchfires glow when the wind lashes them with its cold whip.

“Who is that?” he replied. “Futura, Parody… however you wish to call it. Also: delusion… In short, it is a woman. Every creator of a man first makes himself a woman. I do not believe that humbug about the first human being a man. In the case a male god created the world (which is to be hoped for, Joh Fredersen) then he certainly created woman first, tenderly and revelling in creative playfulness. You can inspect it, Joh Fredersen; it is faultless. A little cold, I’ll give you that. That lies in the material, which is my secret. But she is not yet completely finished. She is not yet dismissed from the workshop of her creator. I cannot make up my mind to do it—you understand that? Completion is like setting something free. I do not want to set her free from me. Because of that, I have not yet given her a face. You must give her that, Joh Fredersen, for you were the one to order the new beings.”

“I ordered machine-men from you, Rotwang, which I can use at my machines. Not a woman that’s some plaything.”

“No plaything, Joh Fredersen, no… You and I, we do not play any more; not for anything. We did it once… Once and never again. Not a plaything, Joh Fredersen, but a tool. Do you know what it means to have a woman as a tool? And a woman like this, faultless and cold? And obedient—unconditionally obedient? Why fight with the Gothics and the monk Desertus about the Cathedral? Send them the woman, Joh Fredersen! Send them the woman when they are on their knees, castigating themselves. Let this faultless, cold woman walk through the rows of them, on her silver feet, fragrance from the garden of life in the folds of her garment (and who in the world knows how the blossoms of the tree, on which the apple of knowledge ripened, smell? The woman is both: Fragrance of the blossom and the fruit)…

Shall I explain the newest creation of Rotwang, the genius, to you, Joh Fredersen? It will be sacrilege. But I owe it to you, for you ignited the idea within me—with your machine-men—of creating… Shall I show you how obedient my creation is? Give me what you’re holding in your hand, Parody!”

“Wait—” said Joh Fredersen rather hoarsely. But the infallible obedience of the being which stood before the two men sanctioned no delay in obeying. It opened its hands in which the delicate bones shimmered silver, and passed the piece of paper, which it had taken before Joh Fredersen’s eyes, from the table to its creator.

“That’s deceit, Rotwang,” said Joh Fredersen.

The great inventor looked upon him. He laughed. The noiseless laughter drew back his mouth to his ears.

“No deceit, Joh Fredersen—the work of a genius! Shall Futura dance for you? Should my beautiful Parody play affectionate? Or sulker? Cleopatra or Damayanti? Should she have the gestures of the Gothic Madonnas? Or the gestures of love of an Asiatic dancer? What hair should I plant upon the skull of your tool? Should she be pure or impudent? Pardon my many words, you man of few! I am drunk, you see? Drunk with being a creator. I intoxicate myself. I inebriate myself on your astonished face! I have surpassed your expectations, Joh Fredersen, isn’t that right? And you do not know everything yet; my beautiful Parody can sing, too! She can read as well. The mechanism of her brain is as infallible as that of your own, Joh Fredersen!”

“If that is so,” said the master over the great Metropolis, with a particular dryness in his voice, which had become more hoarse, “then command her to decipher the plan which you have in your hand, Rotwang...”

Rotwang burst out into laughter, like the laughter of a drunken man. He threw a glance at the piece of paper which he held spread out in his fingers, and wanted to pass it triumphantly to the being which stood beside him. But he stopped in the middle of moving. Open-mouthed, he stared at the piece of paper, raising it nearer and nearer to his eyes.

Joh Fredersen, who was observing him, bent forward. He wanted to say something, to ask a question. But before he could open his lips, Rotwang threw his head up and met Joh Fredersen’s gaze with so green a fire in his eyes that the master of the great Metropolis remained silent. Twice, three times did this green glow flash back and forth between the piece of paper and Joh Fredersen’s face. And during the whole time no sound was perceptible in the room, save the breath that gushed in heaves from Rotwang’s chest as though from a boiling, poisoned source.

“Where did you get the plan?” the great inventor asked at last. Though it was less a question than an expression of startled anger.

“That is not the issue,” answered Joh Fredersen. “It is because of this that I have come to you. In the whole of Metropolis there doesn’t seem to be a single person who knows what to make of it.”

Rotwang’s laughter interrupted him.

“Your poor scholars!” cried the laughter. “What a task you have set them, Joh Fredersen! How many hundreds of printed papers have you forced them to cycle through? I am certain there is no city on the globe, from the building of the old Tower of Babel onwards, which they have not sleuthed through from top to bottom. Oh, if you could only smile, Parody! If only you already had eyes with which you could wink at me! But laugh, at least, Parody! Laugh silverly and invigoratingly at the great scholars to whom the earth under their feet is foreign!”

The being obeyed. It laughed, silverly and invigoratingly.

“Then you know the plan, or what it represents?” asked Joh Fredersen through the laughter.

“Yes, by my poor soul, I know it,” answered Rotwang. “But, by my poor soul, I will not tell you what it is until you tell me where you got the plan!”

Joh Fredersen reflected. Rotwang did not take his gaze from him. “Do not try and lie to me, Joh Fredersen,” he said softly and with a whimsical melancholy.

“Somebody found the paper,” began Joh Fredersen.

“What somebody?”

“One of my foremen.”

“Grot?”

“Yes, Grot.”

“Where did he find the plan?”

“In the pocket of a workman who suffered an accident with the Geyser-machine.”

“Grot brought you the paper?”

“Yes.”

“And the meaning of the plan seemed to be unknown to him?”

Joh Fredersen hesitated a moment with the answer.

“The meaning—yes. But not the plan. He told me he has often seen this paper in the workmen’s hands, and that they anxiously keep it a secret, and that people will flock around the one who holds it...”

“So the meaning of the plan has been kept secret from your foreman?”

“It seems so, for he could not explain it to me.”

“Hmm.”

Rotwang turned to the being, which stood near him with the appearance of an eavesdropper.

“What do you say to that, my beautiful Parody?” he asked.

The being stood motionless.

“Well?” said Joh Fredersen with a sharp expression of impatience.

Rotwang looked at him, jerkily turning his great skull towards him. The glorious eyes crept behind their lids as though they wished to have nothing in common with the stark-white teeth and the jaws of a beast of prey. But, from between the almost-closed eyelids, they gazed at Joh Fredersen as though they searched his face for the door to the great brain.

“What can a man hold you to, Joh Fredersen?” he murmured. “What is a word to you—or an oath, you god with your own laws? What promise would you keep if the breaking of it seemed convenient to you?”

“Don’t blabber on, Rotwang,” said Joh Fredersen. “I’ll keep quiet because I still need you. I know very well that the people who we need are our solitary tyrants. So, if you know something, then speak!”

Rotwang still hesitated, but gradually a smile took possession of his features—a good-natured and mysterious smile which amused even itself.

“You’re standing on the entrance,” he said.

“What does that mean?”

“To be taken literally, Joh Fredersen! You’re standing at the entrance!”

“What entrance, Rotwang? You’re wasting time that does not belong to you...”

The smile on Rotwang’s face deepened to hilarity.

“Do you recall, Joh Fredersen, how adamantly I refused at the time to let the underground railway be run under my house?”

“Indeed. I still know the sum the detour cost me, too.”

“The secret was costly, I’ll give you that, but it was worth the price. Take a look at the plan, Joh Fredersen, what is this here?”

“Maybe a flight of stairs...”

“Quite certainly a flight of stairs. It is very slovenly executed in the drawing, as it is in reality.”

“So you know them?”

“I have the honour, Joh Fredersen, yes. Just come two paces sideways—what is this?”

He had taken Joh Fredersen by the arm, who felt the fingers of the artificial hand pressing into his muscles like the claws of a bird of prey. With the right hand, Rotwang indicated the spot upon which Joh Fredersen had stood.

“What is that?” he asked, shaking the arm which he was holding.

Joh Fredersen stooped down, then straightened himself up again.

“A door?”

“Correct, Joh Fredersen! A door! A very well-fitting and well-shutting door! The man who built this house was an orderly and meticulous person. Only once did he neglect to pay attention, and that he had to pay for. He went down the stairs which are under this door and followed the shoddy steps and passages which connect with them, becoming astray and never finding his way back. It is also not that easy to find them, for those who dwelled there did not put any value on letting strangers penetrate into their domain… I found my inquisitive predecessor, Joh Fredersen, and recognised him at once by his pointed red shoes, which were wonderfully preserved. As a corpse, he looked peaceful and Christian-like, both of which he certainly was not in his life. The companions of his final hours probably contributed considerably to the conversion of the former devil’s disciple...”

He tapped with the forefinger of his right hand upon a maze of crosses in the centre of the plan.

“Here he lies. Right on this spot. His skull must have enclosed a brain which would have been worthy of your own, Joh Fredersen, and he had to perish so despicably because he lost his way one time… Pity on him.”

“Where did he lose his way?” asked Joh Fredersen.

Rotwang looked long at him before speaking.

“In the city of graves on which Metropolis stands,” he finally answered. “Deep below the mole-tunnels of your underground railway, Joh Fredersen, lies the thousand-year-old Metropolis of the thousand-year-old dead...”

Joh Fredersen remained silent. He slowly raised his left eyebrow, while his eyes narrowed. He focused his gaze upon Rotwang, who had not taken his eyes from him.

“What is the plan of this city of graves doing in the hands and pockets of my workers?”

“That is yet to be discovered,” answered Rotwang.

“Will you help me?”

“Yes.”

“Tonight?”

“Very well.”

“I shall come back after the shift change.”

“Do that, Joh Fredersen. And if you want to take some advice...”

“Well?”

“Come in the uniform of your workmen when you come back.”

Joh Fredersen raised his head, but the great inventor did not let him find the time for words. He raised his hand like one who demands and admonishes to silence.

“The skull of the man in the red shoes also enclosed a powerful brain, Joh Fredersen, and yet he could not find his way homewards from those who dwell down below.”

Joh Fredersen reflected. Then he nodded and turned to go.

“Be courteous, my beautiful Parody,” said Rotwang. “Open the doors for the master over the great Metropolis!”

The being glided past Joh Fredersen. He sensed the breath of coldness which came from it. He saw the silent laughter between the half-open lips of Rotwang, the great inventor. He turned pale with rage, but he remained silent. The being stretched out the transparent hand in which the bones shone silver, and, touching it with its fingertips, moved the seal of Solomon, which glowed copper.

The door gave way. Joh Fredersen went out after the being, which stepped down the stairs before him. There was no light on the stairs, nor in the narrow passage. But a shimmer came out from the being, no stronger than that of a green-burning candle, yet strong enough to light up the steps and the black walls.

At the front door the being stood still and waited for Joh Fredersen, who followed slowly behind it. The front door opened before him, but not far enough that he could head out through the opening. He stood still.

From the clump-face of the being, eyes stared at him—eyes as though painted on closed lids, with the expression of calm madness.

“Be courteous, my beautiful Parody,” said a soft, distant voice, which sounded as though the house were talking in its sleep.

The being bowed. It stretched out a hand—a delicate skeleton-hand. Transparent skin was stretched over the slender joints, which shimmered beneath it like dull silver. Fingers, snow-white and fleshless, opened like the petals of a crystal lily. Joh Fredersen laid his hand in it and, in the moment of contact, felt burnt by an unbearable coldness. He wanted to shove the being away from him, but the silver-crystal fingers held him tight.

“Goodbye, Joh Fredersen,” said the clump of head, with a voice full of horrible tenderness. “Give me a face soon, Joh Fredersen!”

A soft, distant voice laughed, as if the house were laughing in its sleep.

The hand left go, the door opened, and Joh Fredersen staggered into the street.

The door closed behind him. In the gloomy wood of the door, the seal of Solomon—the pentagram—glowed copper-red.

***

As Joh Fredersen was about to enter the brain-box of the New Tower of Babel, The Thin Man stood before him, seeming to be even slimmer than ever.

“What is it?” asked Joh Fredersen.

The Thin Man intended to speak, but at the sight of his master the words were lost on his lips.

“Well?” said Joh Fredersen between his teeth.

The Thin Man drew in his breath.

“I must inform you, Mr. Fredersen,” he said, “that since your son left this room, he has disappeared…”

Joh Fredersen twisted awkwardly.

“What does that mean, disappeared?”

“He has not returned home, and none of our men have seen him.”

Joh Fredersen screwed up his mouth.

“Look for him!” he said hoarsely. “What are you all here for? Look for him!”

He entered the brain-box of the New Tower of Babel. His first glance fell upon the clock. He hurried to the table and stretched his hand out to the little blue metal plate.

< Chapter 3 = = = = = = = = = = = Chapter 5 >